- Home

- Shogo Oketani

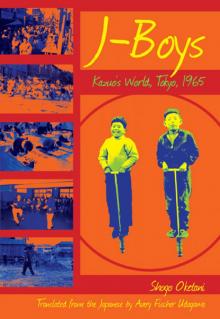

J-Boys

J-Boys Read online

Published byStone Bridge Press P.O. Box 8208Berkeley, CA 94707

TEL 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www. stonebridge.com

J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965

Text © 2011 Shogo Oketani.

All photographs © Shinagawa City, used by permission of Shinagawa City, Japan. Endsheet 1: Tokyo schoolchildren exercising outdoors. Endsheet 2: Schoolchildren posing with their drawings and sketchbooks on Art Day.

Cover and text design by Linda Ronan.

First edition 2011.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Oketani, Shogo.

J-Boys: Kazuo’s world, Tokyo, 1965 / Shogo Oketani; translated from the Japanese by Avery Fischer Udagawa.

p. cm.

Summary: In mid-1960s Tokyo, Japan, where the aftereffects of World War II are still felt, nine-year-old Kazuo lives an ordinary life, watching American television shows, listening to British rock music, and dreaming of one day seeing the world.

ISBN 978-1-933330-92-1.

[1. Family life—Japan—Fiction. 2. Friendship—Fiction. 3. Schools—Fiction. 4. Tokyo (Japan)—History—20th century—Fiction. 5. Japan—History—1945-1989—Fiction.] I. Udagawa, Avery Fischer, 1979– II. Title. III. Title: Kazuo’s world, Tokyo, 1965.

PZ7.O4148Jad 2011

[Fic]—dc22

2011010543

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Leza Lowitz, Yuto Dashiell Oketani, Avery Fischer Udagawa, Ralph McCarthy, Motoyuki Shibata, Ken Rodgers, John Einarsen, Matthew Zuckerman, Trevor Carolan, Joe Zanghi, Suzanne Kamata, Tom Baker, Jasbir Sandhu, Holly Thompson, Susan Korman, Stephen Taylor, Mayumi Allen, Art Kusnetz, Deni Béchard, Donald Richie, Yelena Zarick, and especially the great team at Stone Bridge Press—Peter Goodman, Linda Ronan, Noriko Yasui, and Jeanne Platt—for their tireless efforts to bring Kazuo’s world to life.

The translator would like to thank Shogo Oketani and Leza Lowitz for the opportunity to translate J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965; Dr. Angela Coutts and Dr. Thomas McAuley of The University of Sheffield for valuable feedback; and her husband, Kentaro, and young daughter, Emina, for their vital encouragement and support.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors of the following publications, where stories from this collection previously appeared, sometimes in different form—Wingspan, Kyoto Journal, Yomimono, Another Kind of Paradise: Stories from the New Asia Pacific (Cheng and Tsui)—and to Printed Matter Press.

About the photographs, sidebars, and J-Boys website

All the photographs in this book come from the collection of Shinagawa City (Shinagawa Ward) in Tokyo, where J-Boys is set. They were taken from the mid-1950s through the 1960s and show activities and scenes just as they looked when the stories in this book took place.

You will find many sidebars throughout the text. These contain definitions of Japanese words and information about Japanese things that you may not be familiar with. Words in boldface have sidebars nearby. There is a glossary at the back of the book for quick reference.

Explore the world of the J-Boys, learn more about the author, and find resources for teachers at a special website for this book, j-boysbook.com.

October

The Tofu Maker

Kazuo stood in front of Yoshino’s Tofu, an old metal bowl under his arm.

“Hey there, Kazu-chan,” the owner of the shop said as soon as he had spotted him. “Running errands for your mother again today, eh? That’s a good boy.”

Kazuo grinned shyly at Mr. Yoshino. The older man had tied a towel into a headband around his closely cropped white hair. His eyes shone in his wrinkled face.

Yoshino’s Tofu Shop was in the heart of the West Ito shopping area, in the Shinagawa Ward of southern Tokyo. It had a large tin water tank out front and a stove inside that was black from years and years of boiling soymilk.

Four or five housewives stood before the store with Kazuo. Like him, they had come to buy tofu for the evening’s dinner.

Tofu: Bean curd. Tofu is made from soybean milk that is processed and pressed into soft blocks. Tofu originated in ancient China and then spread to Korea and Japan. It is very low in calories and is often used in vegetarian dishes.

As he took his customers’ orders, Mr. Yoshino dipped his hand into the tank’s ice-cold water. Slowly he drew out blocks of tofu, being careful not to break them. As Kazuo waited for his turn, he watched Mr. Yoshino’s hand. It always looked red and swollen, almost chilblained, from being plunged into the frigid tank day after day. Kazuo did not care much for tofu with its slightly bitter taste and strong soybean smell. He’d leave it on his plate, unless his mother was in a bad mood and threatened that he couldn’t watch TV until he ate it. Then he would hold his breath and gulp it all down without chewing. The good thing about tofu was that you could swallow it without tasting it and you wouldn’t choke.

Kazuo’s father, who worked two train stops away at the Nihon Optics factory, couldn’t get enough tofu. The soft tofu from Yoshino’s store was his favorite, and it rarely failed to appear on the family dinner table. Kazuo’s mother shopped for the day’s dinner on her way home from work, but she couldn’t take the metal bowl with her. So, except on Wednesdays, when Yoshino’s Tofu was always closed, buying tofu in the afternoons was Kazuo’s job. Now that he was nine, his mother told him, he was old enough to manage this sort of thing.

A greengrocer’s stall in a Shinagawa Ward shopping district.

Kazuo thought that he could be a tofu maker someday, if it meant working only in the summertime. But he’d decided that he could never handle it in the winter. He would almost certainly give in to the cold and bring the tofu out of the water too quickly, breaking it.

“Kazu-chan, I think you were next,” Mr. Yoshino told him. Customers streamed toward the shop, but Mr. Yoshino never forgot who was next in line.

-chan: A friendly and informal suffix used for younger kids or girls.

His wife came out of the store and began to take customers’ orders, too. “Well, if it isn’t Kazu-chan!” She smiled. “Hello there!” Like her husband, Mrs. Yoshino had a head of completely white hair, but instead of tying a towel around it, she wore a white cloth folded in a crisp triangle.

“I hear those grades of yours are the best in the class,” Mr. Yoshino said cheerfully and took the metal bowl from Kazuo’s hand. “Your dad was bragging about you the other night. He said you’re going to get into the engineering department of a national university!”

Kazuo pictured his father at Chujiya, the smoky bar by the station, bragging loudly. Father liked to tell jokes and watch TV with the family, but whenever he stopped for a drink after work, he came home loud and irritable. He would start lecturing Kazuo and his little brother Yasuo as they sat watching TV.

“I want you boys to study hard, you hear me? Your old man is working his tail off every day so you can get into good schools.”

“The best grades in the class?” Mrs. Yoshino echoed. “Well, then, your father must be looking forward to your future!”

“I’m not sure they’re the best . . .” Kazuo started to say.

It was true that Kazuo’s grades were good. But he was hardly the top student in his class: section three of the fourth grade at West Ito Elementary School. The top student was probably Keiko Sasaki, who, like Kazuo, lived in company housing for the Nihon Optics factory.

“What are you going to be when you grow up, Kazu-chan?” Mr. Yoshino dipped his hand slowly into the water again.

“I don’t know yet.” Kazuo thought about how his father had grown up on a farm and wasn’t able to go to high schoo

l when the war started. He had gone to vocational school instead. Then, at fifteen, he’d moved to Tokyo and started work at his current company as a factory hand.

The war: World War II, lasting from 1939 to 1945. Almost all the nations of the world were involved. There were two groups fighting each other: the Allies (United States, England, and Soviet Union) and the Axis (Germany, Italy, and Japan). Atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 and large bombing attacks on Tokyo preceded the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

“We’re living in good times now, that’s for sure,” Mr. Yoshino said. “There’s no war on, there’s food to eat, and anybody who wants to study can study to his heart’s content. During the war, there were air raids every day, and we had to worry about what we were going to eat before thinking about schoolwork. Can you imagine? Day in, day out, the first thing on our minds was where we’d get our next meal.”

Every time an adult spoke this way, Kazuo felt lazy and useless. He often got wrapped up in TV and comic books and didn’t study beyond what was absolutely necessary. What really mattered to him right now was figuring out how to run like Bob Hayes, the American who’d won the gold medal in the one-hundred-meter dash at the Tokyo Olympics last year. Watching him on TV—seeing him keep his muscular body low to the ground as he shot out of the starting blocks like a bullet—was something that Kazuo would never forget.

Ever since then, Kazuo and his classmate Nobuo, the son of the local butcher, had been going to an empty lot after school. They would crouch and try to charge into a sprint, just like Bob Hayes. But they often wound up stumbling, or, in trying not to stumble, coming up too soon.

Tokyo Olympics: The Summer Olympics held in Tokyo in October 1964. For the Japanese, the Tokyo Olympics symbolized achieving international acceptance after World War II. The Tokyo Olympics were legendary in Japan for performances by American sprinter Robert “Bullet Bob” Hayes, the Ethiopian marathoner Abebe Bikila, and the Japanese women’s volleyball team. Bob Hayes later became a wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys American football team.

“I wonder if this is just impossible for us Japanese,” Nobuo had recently said in frustration.

“Why would it be impossible?” Kazuo asked.

“We’re built differently, that’s why,” Nobuo said. “The final hundred-meter dash didn’t have a single Japanese athlete in it. The runners were all tall black people and white people. None of them looked like us.”

Kazuo had decided that Nobuo was right. It wasn’t just the hundred-meter dash. Even in judo, a Japanese sport that had just become an Olympic event, the great Inokuma of Japan had lost in the finals to a Dutch athlete.

Japan had lost to America in World War II and to a European athlete at the 1964 Olympics, Kazuo realized. Maybe grown-ups were always telling children to study harder because that would finally make Japan come out on top. Thinking about it this way, Kazuo felt that adults were very selfish creatures.

Mr. Yoshino put a block of tofu into Kazuo’s metal bowl. “You’re still young, Kazu-chan,” he was saying. “So it’s not so simple to predict what you’ll do down the road, is it?” The shop owner placed a thin piece of paper over the top of the bowl to keep the dust off.

“Anyway, the best thing you can do for your mom and pop is grow up healthy, so they won’t have to worry,” Mr. Yoshino added.

Then the tofu maker and his wife both smiled at Kazuo.

He smiled and nodded back.

Several days later, a cold rain fell. Afterward, autumn seemed to come fully upon the town, filling it with cold air. In the midst of the chill, Mr. Yoshino’s hand grew steadily redder. Kazuo could see it swelling up so that it looked like a soggy sweet bun. Even so, Mr. Yoshino’s movements remained exactly the same. Slowly dipping his hand into the water, he carefully brought the tofu up from the bottom of the tank.

Okaasan: Mother, mom, mommy. A very common variation of this is Okaachan or just Kaachan. Ojisan: Grandpa, or what you might call any elderly man whose name you do not know. Ojiichan is a less formal form of the word. -san: San is a suffix added to names to show respect. It is used for both men and women, and can be attached to either the family name or the personal name. For example, the person we call Mr. Tanaka is called “Tanaka-san” in Japan. If his personal name is Hiroshi, his friends may call him “Hiroshi-san.” Japanese people almost always attach a suffix to a person’s name (but not to their own).

One afternoon in mid-October, Kazuo grabbed the metal bowl as always and headed over to Yoshino’s Tofu. But the storefront was completely deserted. The door was closed; a white curtain hung inside, covering the window.

A sign was posted on the old wooden door. There were several characters that Kazuo couldn’t read, but he could make out the words “today” and “closed” so he returned home.

In the kitchen his mother had begun to prepare dinner. Yasuo was sprawled in the living room, watching a TV show called Shonen Jet.

“Okaasan, the tofu store was closed today.” Kazuo returned the metal bowl and ten yen to his mother.

“Really? I wonder if Ojiisan caught a cold,” she said. “The weather turned chilly so suddenly.” Then she added, “If you’ve got homework, Kazuo, finish it up before dinner.”

“Okay,” he said. He took out his kanji-writing notebook and pretended to study at the table. But his eyes were fixed on the TV screen.

Kanji: Japanese characters, or ideograms, originally developed in China. Japanese elementary schoolchildren must learn hundreds of kanji before they reach middle school.

The next day Kazuo raced home. He and Nobuo had spent a long time practicing running in the empty lot, and now he was late for his trip to the tofu maker’s shop. His mother was already home from work.

Kazuo tossed his backpack into the living room and grabbed the metal bowl. “Okaasan, I’m going to the tofu store now,” he called.

“Kazuo.” His mother came toward him. “You don’t have to go today.”

“What? Why?” He stopped in his tracks.

“Ojiisan from the tofu store died yesterday. He had a stroke and collapsed. So starting today, you don’t have to go anymore.”

Not knowing how to respond, Kazuo exhaled softly. Then he slowly removed his shoes.

“Ha-ha! You forgot your job!” Yasuo teased Kazuo, turning on the TV. Shonen Jet appeared in black and white on the screen.

“Niichan, let’s watch,” Yasuo said. But Kazuo remained in the space where the entryway joined the living room, as if frozen.

Niichan: Brother, used to address an older brother in a casual way. Adding “o” at the start of the word is more polite—Oniichan.

At dinner, their father drank hot sake and ate stew without the usual tofu in it.

Sake: An alcoholic beverage made by fermenting rice. Sake (pronounced sah-kay) has a long history in Japan and is used in many rites and celebrations. It can be drunk warm or chilled.

“So the man from the tofu store died, did he?” he said in a low voice.

“He was getting on in years,” Mother said.

“He must have been the only tofu maker who still used well water and boiled the soymilk on a wood stove,” said Father. “What’s going to happen to his shop now?”

“There’s no way his wife can run it by herself,” Mother answered. “They say she’s going to close it. Apparently they had a son, but he died during the war. He was in middle school.”

Father looked surprised at that. “I saw the old man often at the bar, but he never said a word about a son.”

“Yes, well, everyone in the neighborhood knew him as the nicest, smartest boy in the junior high. In early March 1945, there was an air raid. He had to be at a factory instead of school to support the war effort, and the factory was bombed. He never returned.”

Kazuo suddenly remembered what Mr. Yoshino had said: that growing up healthy was the most important thing he could do. He pictured the tofu maker’s red, swollen hand drawing out the tofu.

F

rom now on, I’m going to remember to chew my tofu when I eat it, thought Kazuo. And I’m going to try to do my homework without my mom telling me to do it.

He felt bad that he’d never realized just how good Mr. Yoshino’s tofu really was until now.

Yasuo’s Dog Dreams

Kazuo’s family lived in the Nihon Optics company housing. Companies often built homes on land they owned, renting them out to their employees cheaply.

Kazuo could not really understand why a company would do this. According to his father, it had to do with tax strategy. Father often grumbled about it. “Figuring out ways to get more tax money out of people is the government’s job.”

But Kazuo’s teacher, Mr. Honda, had explained taxes differently. He’d said that they were the reason that children got to go to school.

“Tax money is used for all sorts of things: teachers’ salaries, this school building, even your textbooks.”

That made Kazuo think taxes were a very good thing. Maybe there were good taxes and bad taxes, he decided.

Their neighborhood was encircled by a fence with a sign: Nihon Optics Company Housing. Each of the four complexes was a plain, one-story building made up of five identical housing units in a row.

When you opened the outer sliding door of Kazuo’s house, there was a small entryway with a concrete floor, where everybody took off their shoes before coming inside. The entryway led to the living room, about the size of six tatami mats, with a low, round table in the center. There, Kazuo and his family ate their meals and watched TV. At night, they moved the table to a corner of the room, and Mother and Father laid out their bedding to sleep. The right side of the room opened into a closet that held bedding for the entire family, along with their summer and winter clothing packed in wooden boxes for ventilation. To the rear of the six-mat living room was a four-and-a-half-mat room—Kazuo and Yasuo’s room. There was also a kitchen with two gas burners for cooking. The only bathroom was off the entryway. Naturally, there was no bathtub; every other day the family went to a public bathhouse called Fujita Yu in the center of the West Ito shopping area.

J-Boys

J-Boys