- Home

- Shogo Oketani

J-Boys Page 6

J-Boys Read online

Page 6

Kazuo suddenly pictured the inside of Nishino-kun’s house behind the shopping area. Two weeks ago, they had all gone there to play, taking Yasuo with them. Because Nishino-kun’s parents were both educators, Kazuo had expected to see a white house with a triangular roof, like the houses in American TV shows. He’d imagined carpets on the floor, and chairs and tables, and the family drinking black tea or coffee.

But when Nishino-kun said, “This is it,” and pointed to his house, Kazuo saw instead an aging wooden structure that looked exactly like every other house in West Ito. The exterior walls were covered in cedar boards that had weathered to a dark brown. The roof was a traditional black tile roof, and the front door was no different from the door to Kazuo’s company housing unit: a sliding door with frosted glass windows. It was an extremely ordinary house.

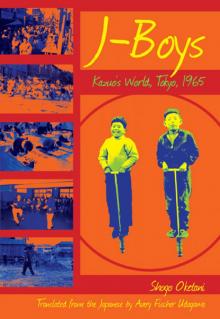

Boys playing near a huge tree in a city park.

Following Nishino-kun, the boys passed the Nishino Residence nameplate on the front gatepost and headed to the door. To the right of the path was a small garden.

“Hey, Nishino-kun, you could have a dog here!” Yasuo told him when he spotted the garden.

“Yasuo, is that the only thing you ever think about?” Kazuo said, and everybody laughed at his exasperated tone.

“Actually, I wish I could have a dog,” Nishino-kun said.

“You should get one!” Yasuo agreed, excited.

But Nishino-kun smiled sadly. “My father won’t let me. He says that having a dog would ruin the garden.”

None of the boys knew why having a dog would ruin the garden. But if Nishino-kun’s university-professor father said it would, they had to believe it.

Nishino-kun used a key to open the old door to the entryway. It slid to the side with a clatter, like a cart traveling through gravel. But when the four boys saw what appeared beyond it, their mouths dropped open.

Nishino-kun’s house was crammed with books.

The entryway was typically a place where people sat or bent down to put their shoes on or take them off. At Nishino-kun’s house, however, the books took up so much space that there was nowhere to sit down. Tall stacks of books were everywhere, lining both sides of the hallway leading into the interior of the house.

Entryway: In a house like Nishino-kun’s, the front door is a sliding panel that opens onto an entryway (genkan) where visitors call to announce themselves or take off their shoes before entering the home (you never wear shoes inside a Japanese house or apartment). Often the rooms are separated by sliding panels (fusuma) that are a lot like movable walls, to be closed for privacy or opened for ventilation.

“Go on in.” At Nishino-kun’s urging, the boys ventured further inside, where the air smelled musty, like old paper. Yasuo clung to the bottom of Kazuo’s sweater, looking as frightened as if he had lost his way in a haunted mansion.

“These sure are huge piles of books,” Kazuo said to Nishino-kun. He tried to sound nonchalant as he gaped at all of the stacks, which seemed to have them surrounded. “Are they all your father’s?”

“Yeah, they’re his,” Nishino-kun answered.

Kazuo noticed that more than half of the books were in foreign languages.

“Why don’t we have some juice or something?” Nishino-kun suggested. He led them into the living room and brought some juice powder, cups, and a kettle of water from the kitchen. Kazuo and the others continued to look about uneasily, not touching the juice that Nishino-kun prepared in front of them.

Nobuo’s eyes were fixed on some sliding doors at the back of the room. A pine tree was painted on them. “Is there a room on the other side of those doors, too?”

“Yeah, that’s my dad’s study. Would you like to see it?” Nishino-kun stood up and opened the doors.

Kazuo saw yet another room overflowing with books. It did not look like it was even used by humans. With just a tiny bit of afternoon sunlight streaming in through an opening in the curtains, it looked more like something from a science-fiction movie.

All the walls of the six-mat room had large bookcases placed against them. Books that did not fit into the bookcases were piled into towering stacks on the floor. Kazuo thought they looked like skyscrapers built by aliens. He could even picture a creature with an oversized head and detached eyeballs sitting at the desk in the middle of the room and ruling over the alien city.

And so, two weeks later, as the boys sat in the empty lot talking about their futures, Nobuo was obviously remembering all the books in Nishino-kun’s house, too. But when he asked Nishino-kun if he were going to be a college professor, Nishino-kun shook his head. “That would be impossible. I’m not very smart, you know.” He wrapped his long, skinny arms around his legs and looked away.

“You’re smart,” Kazuo spoke up.

“Yeah,” Nobuo chimed in. “If you don’t want to be a college professor, then what do you want to do?”

Nishino-kun stayed silent. He just kept staring off at the wilted, brown grass.

Kazuo exchanged glances with the others. He couldn’t help feeling annoyed with Nishino-kun. His family was well off, at least compared to the rest of them. Both of his parents were teachers, and he had a ton of books in his household. He ought to be able to do anything he wanted when he got older.

“Akira!” someone said sharply.

Kazuo turned around. A thin man wearing a gray suit and glasses was coming toward them.

“Otohsan!” Nishino-kun scrambled to his feet.

Nishino-kun’s father approached the boys with deliberate strides. “These must be your friends.” He held a bulging briefcase, and his forehead was furrowed as he glanced at Kazuo and the others.

“Yes,” Nishino-kun answered in a small voice.

“Is your homework done yet?”

“No, not yet.” Nishino-kun hung his head.

“Well then, instead of loitering in a place like this, I want you to go straight home and study. Do I make myself clear?” Nishino-kun’s father spoke in a low, stern voice.

Nishino-kun nodded, then picked up his backpack.

“I’ll see you tomorrow, everyone,” he muttered. He hunched his shoulders as he followed his father out of the lot.

“He’s heading home to that house of his,” Minoru murmured.

Kazuo knew exactly what Minoru was saying. In that house of his, Nishino-kun probably had to study under the stern eye of his father. Kazuo himself studied while being nagged by his mother. But that was in the living room with the TV on, and plenty of ways to escape her instructions. Nishino-kun’s house, which seemed to exist for the sole purpose of storing books, probably didn’t have any escape routes.

A chilly wind had begun to blow though the empty lot. Without anybody saying much of anything, Kazuo, Nobuo, and Minoru got up and put on their backpacks.

“Well, see you,” Minoru said.

“Yeah, see you tomorrow,” Nobuo answered.

“Bye.” Kazuo waved and started for home. As he walked, he thought again about Nishino-kun and how he’d refused to say anything about his future plans. Why had he acted so stubborn? Kazuo wondered. Then he remembered how Nishino-kun acted in class, all dreamy with his unusual way of thinking that Mr. Honda seemed to admire. Nishino-kun was different, that was for sure. But maybe like the other boys, he did dream about his future. It was just that he had trouble expressing that dream in words because of the mountains of books in his house, or because of that low, stern voice that told him to “go straight home and study.”

Kazuo smiled when he remembered what he himself had said about what he wanted to be when he grew up. He hadn’t answered with his father’s words: “Kazuo will enter a national university, get a Ph.D., and work at a top company!” Instead he’d said the first thing that had popped into his head.

“I think I’ll be the captain of a ship that goes to foreign countries.”

“That’s cool,” Minoru had said. The others had grinned and nodded.

Kazuo was nearly home. The sun had set and the sky was nearly bla

ck now.

Being the captain of a ship does sound cool, Kazuo thought. He wondered if he’d really do it. He wondered what the future held for any of the J-Boys.

December

What Wimpy Ate

By now Kazuo knew a lot about American foods from watching American TV shows. From school lunch, he’d learned to twirl his spaghetti around inside his spoon. When he ate spinach, he imagined getting strong like Popeye. And when he had cheese, he felt a bit like the mouse in Tom and Jerry cartoons. The miruku he had to drink was as disgusting as ever, of course.

Popeye: An American comic strip and cartoon hero who speaks with a raspy voice and gains super-strength from popping open and eating whole cans of spinach. Popeye the Sailor, with the Japanese title Popai, was shown in Japan from 1959 to 1965. Tom and Jerry: Cat and mouse cartoon characters famous for their wild chases and frantic fights. The first Tom and Jerry cartoon appeared around 1940. In Japan, Tom and Jerry was broadcast from 1964 to 1966.

But there was one food that Kazuo could not figure out. That was the food that had meat between two round pieces of bread. It was eaten by Wimpy, a fat man who often appeared on Popeye the Sailor.

“I’ll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hanbaagaa today,” Wimpy always said.

Why next Tuesday, Kazuo did not know, but a hanbaagaa had to be delicious if it was worth borrowing money for.

“I bet it’s some kind of croquette roll,” Nobuo had told Kazuo.

A croquette roll, which consisted of a crispy croquette sandwiched between two halves of a bread roll, was certainly delicious. But a croquette roll was hardly the sort of food you’d borrow money for.

Croquette: Korokke in Japanese. A deep-fried breaded patty of minced meat or fish mixed with potato, eggs, and breadcrumbs. Korokke are filling, cheap, and convenient, one of the original “fast foods” in Japan.

So Kazuo wasn’t so sure about Nobuo’s theory.

Kazuo tried asking his friend Nishino-kun, but he had no idea either. “I’ll ask my father sometime.”

Kazuo didn’t think that Nishino-kun’s stern father would know about Wimpy’s hanbaagaa. But Nishino-kun’s father was a college professor, after all, so Kazuo allowed himself a faint hope.

And one morning, two days later, Nishino-kun excitedly informed the other boys that he had found out what a hanbaagaa was.

“My father says it’s really called a hanburugu steak,” Nishino-kun said, taking a slip of paper from his backpack.

“Hanbaagaa. Alternative name for hanburugu steak. A grilled patty of ground beef mixed with flour, onion, and similar ingredients.”

Kazuo felt confused about the word “steak.” He knew what “beefsteak” was: a thick slab of grilled beef that was served on a plate. But that was completely different from the food Wimpy picked up with his hands to eat.

“It sounds like a breaded ground pork patty,” Nobuo said.

Kazuo shook his head. “No, it’s different from a pork patty.” He was certain about that much.

Meanwhile, the weather had turned cold. At Kazuo’s house, the heated table, or kotatsu, appeared in the living room in December after being shut away from spring through autumn. There was nothing quite like sitting at the kotatsu, a low table with an electric heater attached to its underside. Coming in from the cold outdoors and putting your legs and arms underneath the blanket that covered the table was like dipping yourself into rays of warm sunshine. Kazuo and Yasuo spent so much time sitting there, with their limbs tucked underneath and their chins resting on the tabletop, that their mother would say, “You’re going to sprout roots and be stuck there, even when spring comes.”

Kotatsu: A low, heated table. The top of the table is only 14 inches off the floor. The top lifts off, and over the frame you spread a large blanket. You sit on the floor and tuck your legs under the blanket, beneath the table, where there is an electric heating element. Most Japanese homes in Kazuo’s time did not have central heating, so a kotatsu was one of the only ways to stay warm during the winter. Families would gather around the kotatsu for meals, games, and homework, since it was often the warmest place in the house.

But the boys continued to linger at the kotatsu, even after their parents left for work in the mornings. They would jump out and run off to school only when they were almost late.

Part of the reason for this was that if they arrived too early, their classrooms would be freezing cold.

Every classroom at the school had a coal-burning stove. But the teacher didn’t put the coal in and light the stove until right before first period. Plus, the boys in Kazuo’s class liked daring each other to see who could wear shorts to school the longest. As long as their game continued, the cold of the winter mornings would seem even worse.

On the first Saturday afternoon of December, Kazuo and Yasuo arrived home from school to find a pair of women’s wooden sandals in the entryway.

Grandmother! Kazuo thought, hearing an older woman’s lively voice on the other side of the door to the living room.

“I think Obaachan’s here!” Yasuo cried.

Obaachan: Grandma. Similar to other name forms, this is a less formal form of Obaasan, or Grandmother. Nagauta: A form of traditional Japanese vocal music. It was originally used in Kabuki (historical costume drama) to comment on the action from the side of the stage. The nagauta singer often plays a shamisen, a three-stringed instrument that sounds a bit like a banjo.

Grandmother was taking lessons twice a month in nagauta, traditional folk singing. She often stopped by Kazuo’s house when her lessons fell on a Saturday.

This grandmother was their mother’s mother, Tatsue, and Kazuo was happy that she had come. But he was too old now to show excitement like Yasuo. He intentionally removed his shoes slowly before stepping into the living room.

“Hello there, Kazuo. I think you’ve gotten taller again!” Grandmother, who was wearing a light brown kimono with a deep green haori jacket, turned to look at him from the kotatsu.

“Maybe I’ve gotten taller. I’m not sure.” Kazuo sat down next to his grandmother. He smelled something that reminded him of herbal mouth-freshening drops. He thought the scent was from a small sachet in Grandmother’s obi.

Haori: A lightweight silk jacket worn over a kimono to protect it and keep it clean and dry. Obi: A sash for a kimono. Obi for women come in many different widths, colors, and patterns and can be over 12 feet long. Wide obi are for formal occasions, and colorful obi are for younger, unmarried women. An obi requires a lot of practice to put on and tie correctly (often an assistant is needed!).

“Kazuo, did you greet Obaachan properly?” Mother asked, bringing a plate of tangerines from the kitchen.

“You sure did, didn’t you, Kazuo?” Grandmother said. She smiled as if they were sharing a joke.

Mother sat across from Kazuo and gave him a look. “Don’t spoil him too much, Okaasan. He talks back and ignores me quite enough these days without your encouragement.” Mother lightly slapped the top of Kazuo’s hand as he reached for a tangerine.

“Wash your hands first. Then you can eat.”

“My, my, you have a strict mother, don’t you?” his grandmother said. He got up to wash his hands and then returned to the kotatsu.

“Here, Kazuo.” Grandmother handed him a peeled tangerine.

“Koji-san is late today, isn’t he?” Grandmother said, asking about Father.

Businesses closed for the week at noon on Saturdays, just like school. Father was usually home before one o’clock.

“They have extra work to finish before the end of the year. He won’t be home till late afternoon,” Mother said.

“Too bad,” Grandmother said, sounding disappointed. “I was hoping to take everyone out for lunch.”

“You mean it? All right!” Yasuo said.

“But we should wait until another time since your father isn’t home. It’s more fun when we can all go together.”

Yasuo’s shoulders instantly drooped.

Grandmother

laughed and slapped his back.

With his chest hunched and the chin of his sulky face resting on the tabletop, Yasuo looked like a deflated rubber doll.

“Well, how about this. I’ll take you and Kazuo on a date, just the three of us.”

“A date?” Yasuo blinked in surprise.

“What, you don’t like that idea?”

“It’s not that I don’t like it, but it sounds a little embarrassing.”

“Well, all right then.” Grandmother put her arm around Kazuo’s shoulders. “Kazuo and I will just have to go all by ourselves.”

“Hey, that’s not fair!” Yasuo cried. “You have to take me with you, too!”

Grandmother laughed again. “All right then, let’s get going while it’s still warm out.”

Before long the three of them were walking through the fancy Ginza district downtown, which was decked out in red, gold, white, and green to celebrate the Christmas season. There were Christmas trees covered in miniature lights everywhere, and the song “Jingle Bells” was playing down every street.

Ginza: An upscale shopping district in downtown Tokyo. A trip to Ginza was a very special event (the area is several train stops north of where Kazuo lives). The Mitsukoshi Department Store was (and still is) a landmark building, filled with floors of expensive merchandise and lots of restaurants where shoppers can eat and relax.

“Yasuo, hold tight to my kimono so we don’t lose each other,” Grandmother said as they continued on their way to the restaurant. She dropped a one-hundred-yen bill into a donation pot at the Sukiyabashi intersection, where a Salvation Army chorus was singing “Silent Night.”

Soon, they reached the cafeteria on the eighth floor of the Mitsukoshi Department Store. The place was packed, with not one single seat available. There were already two families waiting in line ahead of them, sitting on chairs outside the cafeteria.

J-Boys

J-Boys